Forecasting what the weather will be like tomorrow can be difficult. Now imagine forecasting the weather on the world’s tallest peak, Mount Everest. That’s exactly what students in Lyndon’s Atmospheric Science department did this spring. For the second year in a row, ten students, led by Dr. Jay Shafer, provided Mount Everest weather forecast support for an expedition. What an amazing experiential learning opportunity!

Students were able to apply the weather forecasting concepts that they learned in the classroom to forecasting the weather on Mount Everest.

The New England-based climbing team that Lyndon provided weather forecast support for successfully completed their mission of doing high altitude archaeology near 27,000 feet elevation. The daily weather forecasts helped them to stay safe, particularly ahead of heavy snowfall on Tuesday, May 9.

Mount Everest Weather Forecast Challenges

When forecasting for Mount Everest, there are two weather forecast challenges: high winds and heavy snowfall. These create dangerous climbing conditions. Typically, both wind speeds and snowfall are low during the second and third weeks of May. Not coincidentally, May 17 to May 23 is when the highest number of summits occur each year.

Forecasting the weather in the U.S. is a luxury compared to Mt. Everest.

-Scott Myerson, senior

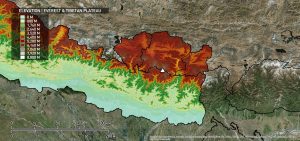

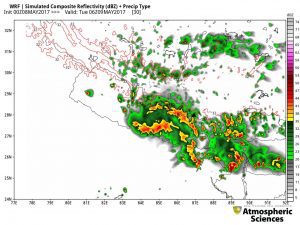

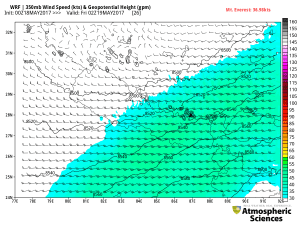

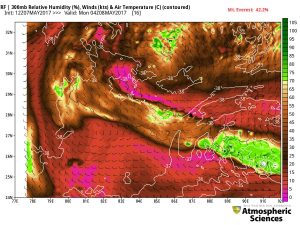

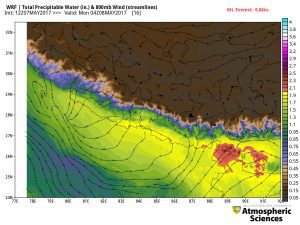

New this year, Lyndon ran an in-house 4 km (high-resolution) Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model over Everest. This helped to tease out weather forecast details, such as wind direction over the complex terrain (see the elevation map, below) and simulated radar, that were not apparent or available with other lower-resolution weather models.

What makes forecasting for #Everest2017 successful? Battle-tested forecasters combined with model data, including our own in house WRF model pic.twitter.com/d6lLPmfrUZ

— Eric Weglarz (@WeatherEric) May 9, 2017

One weather forecast expected wind direction to bring in drier air aloft, helping to keep clouds and snowfall at bay. While the monsoon moisture remained fairly high in the lowlands to the south, the wind flow was generally expected to keep most clouds and any precipitation south of the summit.

@lyndonweather convection cycled much earlier in the day, but multiple MCS developed pic.twitter.com/4Ahfvacv5B

— Jason Shafer (@jayshaferwx) May 17, 2017

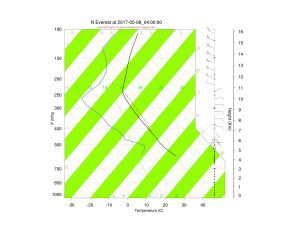

On another day, the WRF simulation forecasted that a mesoscale convective system (MCS), a complex of thunderstorms, could impact the summit. Temperatures were cold enough there for possibly significant snowfall. It turned out that precipitation occurred earlier in the day than was forecast, but there were mesoscale convective systems.

“Everest was not only a high-stakes forecast, it also had high rewards. Hearing about our team’s safety and success was highly rewarding and motivating,” said sophomore Francis Tarasiewicz. Scott Myerson, a senior, summed up the overall experience well: “Forecasting the weather in the U.S. is a luxury compared to Mt. Everest.”